One of the most compelling aspects of playing progressive rock is how the genre encourages you to turn simple concepts into something new. Nowhere is this more evident than with simple major triads, a sound you’ll hear used again and again in nearly every type of rock music.

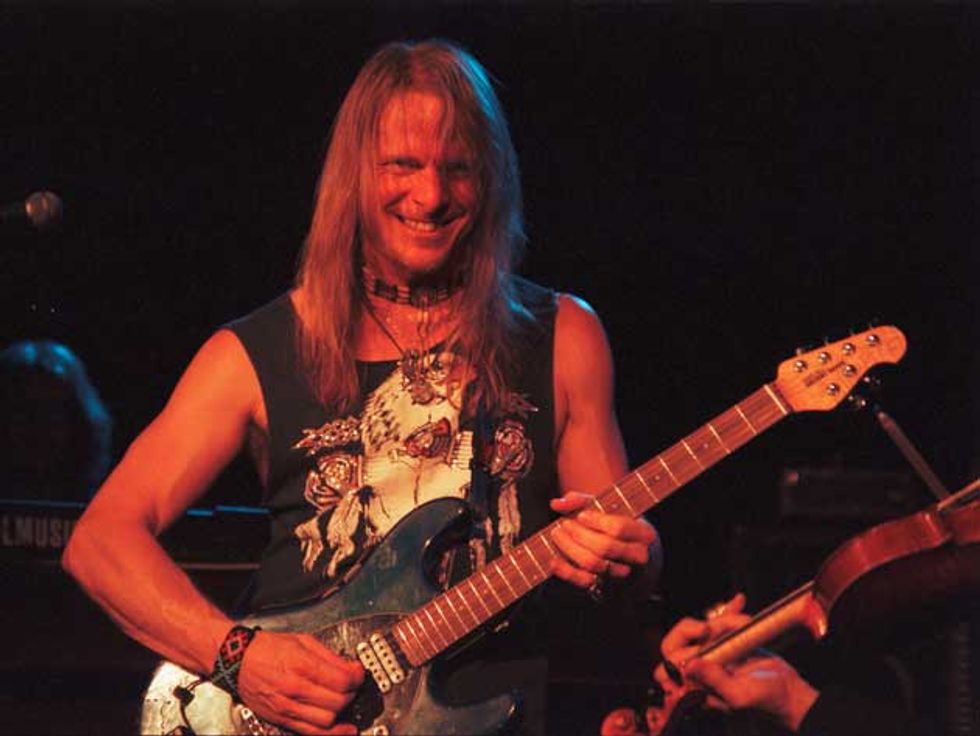

A perfect example of someone who uses triads extensively is the great Steve Morse. He has worked in many enduring bands, including the Dixie Dregs, Kansas, and Deep Purple, as well as the prog supergroup Flying Colors. If you aren’t familiar with Steve’s work, check out “The Introduction” below to see what he’s all about.

Let’s get some basic terms and definitions out of the way. The first thing to know is that a triad is a three-note chord that most often consists of the root, 3, and 5 of a given key. Imagine you are in the key of E major (E–F#–G#–A–B–C#–D#). Take the first, third, and fifth notes of the major scale (E, G#, and B, respectively) and you have a major triad. It doesn’t matter what order, or inversion, the notes are in, the resulting triad will have the same function.

In Ex. 1, you can see the notes of an E triad played up the neck in inversions against an E bass note. If you look closely, you’ll see each chord stab contains only the notes E, G#, and B.

It’s possible to extract more triads from an E major scale, by simply starting on any other note. For example, if you start on F#, then take a note a third higher (A), and a note a fifth higher (C#), you’ll have an F#m triad. This concept goes a bit beyond what we’ll focus on in this lesson, but being aware of basic major-scale harmony is an essential skill.

While it’s possible to use all these triads, to keep this lesson simple, I’ll stick to major triads. This is far from limiting—in fact, you’ll find that 90 percent of rock bands using these concepts also just stick to good-old major triads!

The following examples (Ex. 2 and Ex. 3) combine E, A, and B major triads over an E bass note to create more of a riff. This has a classic E major sound because it uses all the notes of the major scale.

One of the quickest ways to take these triads and turn them into something, well, more prog, is by using modal interchange. You can think of this as “borrowing” chords from other keys to imply a modal sound. In our previous examples, we’ve stuck entirely to the notes that are diatonic to the key of E. What would happen if we looked at chords in the key of A?

There are also three major triads in the key of A—A, D, and E. Two of these triads also occur in the key of E, but D does not. When viewed from the perspective of an E bass note, this outlier implies an E Mixolydian (E–F#–G#–A–B–C#–D) sound. In Ex. 4, you can hear this in action.

When comparing E major and E Mixolydian, the D triad is characteristically Mixolydian, as its root (D) isn’t found in the E major scale. So when writing riffs in E major, if I include a D major triad, that’s borrowing a chord from the E Mixolydian mode. The rule to remember: When you play a major triad a whole-step below the root, it yields a Mixolydian sound. Ex. 5 offers a taste of this.

It’s also possible to experiment with major triads from other modes to see how they work against specific bass notes. For example, the E Aeolian mode (E–F#–G–A–B–C–D) contains the same notes as G major (G–A–B–C–D E–F#). In Ex. 6, I’m using G, D, and C major triads from the key of G major to imply an Aeolian sound against the E bass note.

Ex. 7 is a Van Halen-sounding riff that incorporates triads from both E Aeolian (C, D, and G) and E Mixolydian (D, E, and A). Combining triads this way is a huge part of Eddie’s style, and can be heard on many of his most famous riffs, including “Panama” and “Jump.”

Our final example (Ex. 8) is inspired by John Petrucci. This uses all the triads we’ve covered so far, and adds an F major triad (borrowed from E Phrygian, E–F–G–A–B–C–D)—and even an Eb major triad. The latter makes a tangy half-step passing chord into D.

You can do a lot with this concept, and there’s really no right or wrong way to pursue it. The key is to experiment and find sounds you like. So, get playing and see how progressive you can get … good luck!